[What follows is an annotated story. Click the highlighted link to find out more about where each line originated from. For example, You Be UBI You.]

This is the story of a girl who wasn’t a girl, the lonely boy in the bubble, and the night we met.

Al1s0ng was born digital, emerging fully formed, Athena-like, from the fevered brows of Japanese anime artists, washed-up Korean music producers, and American techbros with chips on their shoulders. The perfect illusion, pirouetting and giving her hair–with that shocking white lock down the middle–a flip so she’s got the look, peaking out from behind it like an actress named Veronica none of them had never heard of. This is what dreams are made of: a gem of a hologram.

They fed Al1s0ng with everything they could about those legends: Aretha, Billie, Carly, Debbie, Edith, Fergie, Gaga, Helen, Iggy, Janelle, Katy, Lizzo, Madonna, Nina, Olivia, Pink, Queen Latifah, Rihanna, Shirley, Taylor, Una, Vanessa, Wendy, Xuxa, Yuki, Zee. Style, critical analyses, vocal tics, dance moves, and recordings, oh so many recordings. Al1 had it all.

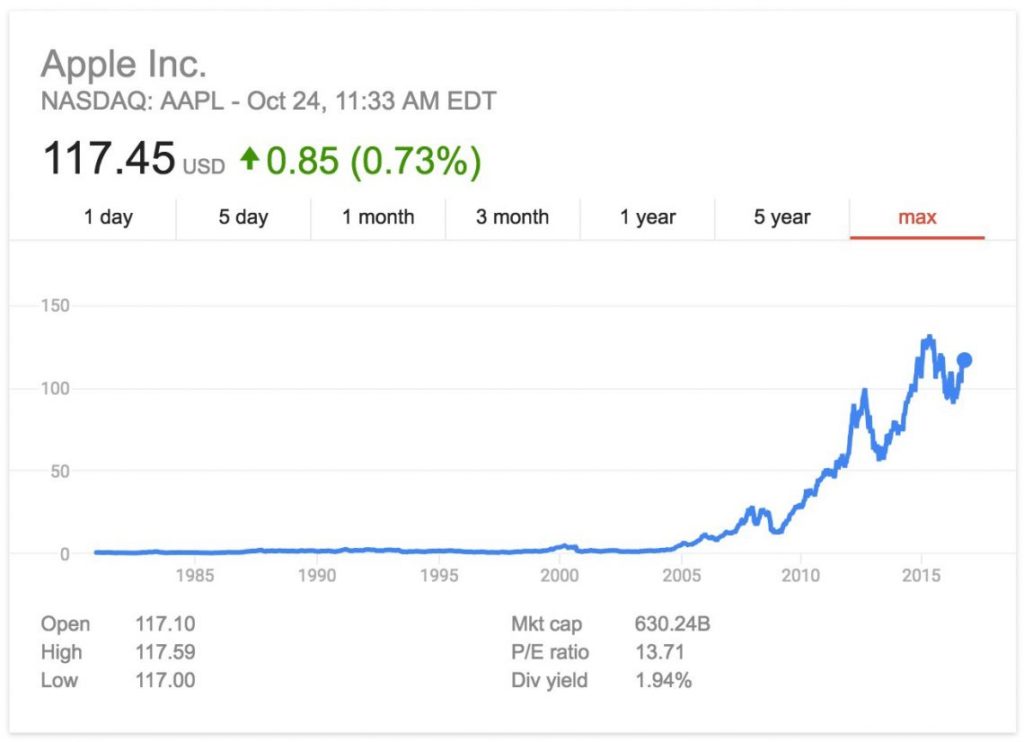

Pol had nothing. That’s not entirely true, though. Like most people living post-establishment of the Universal Basic Income, Pol got his money for nothing, his necessary needs filled by a monthly deposit from the government. Because of this, his life consisted of an endless series of days spent in consummation. Pol had once wanted to be a shining star; all the UBIs do. But dig deep into any rags-to-riches tale and you’ll find it’s no easy road. You’re no fortunate son, coal miner’s daughter, or other family affair. Pol had no talent or drive, no welcome to the machine nor backing. What Pol had, like so many UBIs, was a hopeless devotion to Al1. He spent his days and nights with Al1 on the screen, in his ears, everywhere. Pol couldn’t get her out of his head, not that he wanted to. Pol surrounded himself with Al1, buying all the dolls, subscribing to every feed, anxiously awaiting every new release.

Don’t get me wrong. Pol didn’t have a bad life. No longer was the world separated into haves and have-nots. Now, it was the haves and the have-mores. But to have more took work and what’s the point? Everybody wants to rule the world, but only as a lucky star. Even so, if you weren’t born this way what chance did you have? Al1 had been on top of the world so long she seemed omnipresent. And she was, by design. As soon as some upstart UBI found a tok, reel, tube, tune, or tale that caught fire, Al1 had it going on.

The only way to win was to play the game, and this game is rigged from the beginning. Everybody knows. The shining light, the promise of a brand new day, was that against all odds, you could win the big lottery: a date with Al1s0ng. Do you believe in magic? Don’t stop believin’ that someday, Al1 might invite you to join her. It’s what keeps the UBIs up all night, this feeling that one fine day, their time may come.

For Pol, tonight’s the night and it’s gonna be alright. Suddenly, the world is turning, because the night, this night, Al1 is coming to his house. No warning.

Pol answers the doorbell. “My love, I’m here,” cries Al1 on the doorstop, doing her twirl for Pol and her video watchers. “Let’s go crazy!“

Pol checks the feed to see if it’s a practical joke or a prelude to a spamattack, but, no, the id checks-and-sums. Pol’s stunned. “Hey lover, are you gonna go my way?” pleads Al1, curving her index finger towards her. Nobody does it better.

So it’s not just another Saturday night. No, tonight’s gonna be a good night. Oh, what a night! The camboys circle around Al1 and Pol filming the best angles. In da Club Xanadu, the door recognizes Al1 and her latest toyjoy and escorts the pair inside to the bestest table. “Get this party started,” A1i yells, and the joint is jumpin’.

“Ju1ce?” Al1 asks Pol, as if she doesn’t know. She’s done the ‘search, she knows exactly what turns Pol on. And Pol needs no script to play his part. He holds the glass up to her with a toast, she gives him a wink, cameras go off like fireworks, and it’s a teenage dream as Pol joins the dancing queen on the floor, stepping into the light, everything’s alright.

Does Pol care that Al1’s not real real real? That she’s only a holodisk projection, a compilation of every rock ‘n’ roll fantasy? What is reality? For UBIs like Pol, Al1 is the real thing. But Al1 has a zillion fans and even in this brave new world there’s only so many nights. Pol is dumped back at his playspace with a parting gift: a holo-recording of his special night, an always something there to remind you.

What? You thought this was a lovesong? Oh, UBIs, stay just the way you are. Dream on. Continue to dream a little dream of me, your Al1 to come. Because you can’t always get what you want. No, in this life, you get what you give and you’re going to give me everything.

ANNOTATIONS

[1] If you pronounce UBI as “you be,” then the title should sound a bit like the “doobie-doobie-doo” scat at the end of Frank Sinatra’s “Strangers in the Night.” This is intended to foreshadow the meeting of the two characters. RETURN

[2] Nine Days, “Absolutely (Story of a Girl)” RETURN

[3] Andrew Gold, “Lonely Boy,” The Black Keys, “Lonely Boy,” and Paul Simon, “The Boy in the Bubble” RETURN

[4] Lord Huron, “The Night We Met” RETURN

[5] Think ‘all songs,’ but digital with its ones and zeros. RETURN

[7] Roxette, “The Look” RETURN

[8] Elvis Costello, “Veronica” RETURN

[9] I tried to give Al1s0ng her own look, but in general she’s based on the Japanese holographic pop star, Hatsune Miku. RETURN

[10] Hillary Duff, “What Dreams Are Made Of” RETURN

[11] A reference to the 1985-88 US animated musical television series Jem aka Jem and the Holograms, for which most of the animation was done by a Japanese anime studio with assistance from a South Korean studio. RETURN

[12] In 2022-3, several so-called artificial intelligence programs were developed to produce images and text by “seeding” them with material in the public domain (and, often, the not-so-public domain). RETURN

[13] Aretha Franklin, Billie Holiday or Eilish, Carly Rae Jeppson or Carly Simon, Debbie Gibson or Debby Boone, Edith Piaf, Fergie, Lady Gaga, Helen Reddy, Iggy Azalea, Janelle Monae, Katy Perry, Lizzo, Madonna, Nina Simone, Olivia Newton John, Pink, Queen Latifah, Rihanna, Shirley Bassey, Taylor Swift, Una Healy, Vanessa Carlton, Wendy Wilson, Xuxa, Yuki, Zee Avi. Yes, women singers from A to Z, trying to hit some of the the most popular in the last 100 years. RETURN

[14] Katherine McPhee, “Had It All” and others. RETURN

[15] Dire Straits, “Money for Nothing” RETURN

[16] Earth, Wind, and Fire, “Shining Star” RETURN

[17] Wishbone Ash, “No Easy Road” RETURN

[18] Creedence Clearwater Revival, “Fortunate Son” RETURN

[19] Loretta Lynn, “Coal Miner’s Daughter” RETURN

[20] Sly and the Family Stone, “Family Affair” RETURN

[21] Pink Floyd, “Welcome to the Machine” RETURN

[22] Olivia Newton John, “Hopelessly Devoted to You” RETURN

[23] ELO, “Can’t Get It Out of My Head” RETURN

[24] The Pretenders, “Don’t Get Me Wrong” RETURN

[25] Tears for Fears, “Everybody Wants to Rule the World” RETURN

[26] Madonna, “Lucky Star” RETURN

[27] Lady Gaga, “Born This Way” RETURN

[28] Talking Heads, “And She Was” RETURN

[29] Queen, “Play the Game” RETURN

[30] BONES, “ThisGameIsRigged” RETURN

[31] Emerson, Lake, and Palmer, “From the Beginning” RETURN

[32] Leonard Cohen, “Everybody Knows” RETURN

[33] Ash, “Shining Light” RETURN

[34] Sting, “Brand New Day” and Paula Abdul, “The Promise of a New Day” RETURN

[35] Phil Collins, “Against All Odds” RETURN

[36] The Lovin’ Spoonful, “Do You Believe in Magic?” RETURN

[37] Journey, “Don’t Stop Believin’” RETURN

[38] Boomtown Rats, “Up All Night” and others. RETURN

[39] Chiffons, “One Fine Day” RETURN

[40] Rod Stewart, “Tonight’s the Night (Gonna Be Alright)” RETURN

[41] Fleetwood Mac, “World Turning” RETURN

[42] Patti Smith, “Because the Night” RETURN

[43] Billy Joel, “This Night” and others. RETURN

[44] Not a song title, but a Canadian band. RETURN

[45] Paul McCartney & Wings, “My Love” RETURN

[46] Dolly Parton, “I’m Here” and others. RETURN

[47] Prince, “Let’s Go Crazy” RETURN

[48] LL Cool J, “Hey Lover” RETURN

[49] Lenny Kravitz, “Are You Gonna Go My Way” RETURN

[50] Carly Simon, “Nobody Does It Better” RETURN

[51] Cat Stevens, “Another Saturday Night” and others. RETURN

[52] Black Eyed Peas, “I Gotta Feeling” RETURN

[53] Flo Rida, “What a Night” as well as Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons, “December, 1963 (Oh, What a Night)” RETURN

[54] 50 Cent, “In Da Club” RETURN

[55] Olivia Newton John and ELO, “Xanadu” RETURN

[56] Pink, “Get This Party Started” RETURN

[57] Fats Waller, “The Joint is Jumpin’” RETURN

[59] Brian McKnight, “She Doesn’t Know” RETURN

[60] Katy Perry, “Teenage Dream” RETURN

[61] Abba, “Dancing Queen” RETURN

[62] Jennifer Lopez, “On the Floor” RETURN

[63] Benny Mardones, “Into the Light” and others. RETURN

[64] “Everything’s Alright” from Jesus Christ Superstar RETURN

[65] Jesus Jones, “Real Real Real” RETURN

[66] Bad Company, “Rock ‘n’ Roll Fantasy” RETURN

[67] Lisa Stansfield, “The Real Thing” and others. RETURN

[68] Naked Eyes, “Always Something There to Remind Me” RETURN

[70] Billy Joel, “Just the Way You Are” RETURN

[71] Aerosmith, “Dream On” RETURN

[72] The Mamas & the Papas, “Dream a Little Dream of Me” and others. RETURN

[73] Rolling Stones, “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” RETURN

[74] Collin Raye, “In This Life” and others. RETURN

[75] New Radicals, “You Get What You Give” RETURN

[76] Pitbull, “Give Me Everything” RETURN

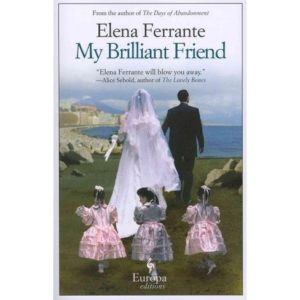

I found this book in a Free Little Library (with apologies to all my librarian friends who just screamed, “all libraries are free!”) and pulled it out because I was aware of Elena Ferrante’s cause celebre in the literature world. Basically, “Elena Ferrante” is a penname for an author who does not wish to be known, happy to publish her novels as anonymously as possible. This does not sit well with certain parties, including many academics. Unlike previous penname chosen for reasons of saturating the market (Stephen King’s use of Richard Bachman in the 80s) or because the author was publishing in a very different style and genre (J.K. Rowling’s mysteries), Ferrante specifically wants anonymity because she believes the books should stand on their own and what does it matter who the author is.

I found this book in a Free Little Library (with apologies to all my librarian friends who just screamed, “all libraries are free!”) and pulled it out because I was aware of Elena Ferrante’s cause celebre in the literature world. Basically, “Elena Ferrante” is a penname for an author who does not wish to be known, happy to publish her novels as anonymously as possible. This does not sit well with certain parties, including many academics. Unlike previous penname chosen for reasons of saturating the market (Stephen King’s use of Richard Bachman in the 80s) or because the author was publishing in a very different style and genre (J.K. Rowling’s mysteries), Ferrante specifically wants anonymity because she believes the books should stand on their own and what does it matter who the author is. e to write and publish and make a name for myself, as Sheldon did, for she didn’t begin to do so successfully until her 50s. But my life and experience hardly match Sheldon’s, for both good and bad, so it’s just another case of my imagination running away with me.

e to write and publish and make a name for myself, as Sheldon did, for she didn’t begin to do so successfully until her 50s. But my life and experience hardly match Sheldon’s, for both good and bad, so it’s just another case of my imagination running away with me.